People > Talent

I have a strong belief that the people who make up your organization are the lifeline of the organization itself. This goes beyond “talent,” which seems to be quite the buzzword these days with articles about crafting your robust talent strategy and the state of web3 talent amassing around us nearly each week. Talent is important because it can make something work, but people are key to making something great.

Talent gets people in the door.

I’m not swearing off the word “talent” or forgetting my past as a member of a corporate talent acquisition team. An intentional and strong talent strategy is important for organizations as they strive toward growth, but it is useless if it is accompanied by little or no thought toward actively caring for those individuals from onboarding to offboarding.

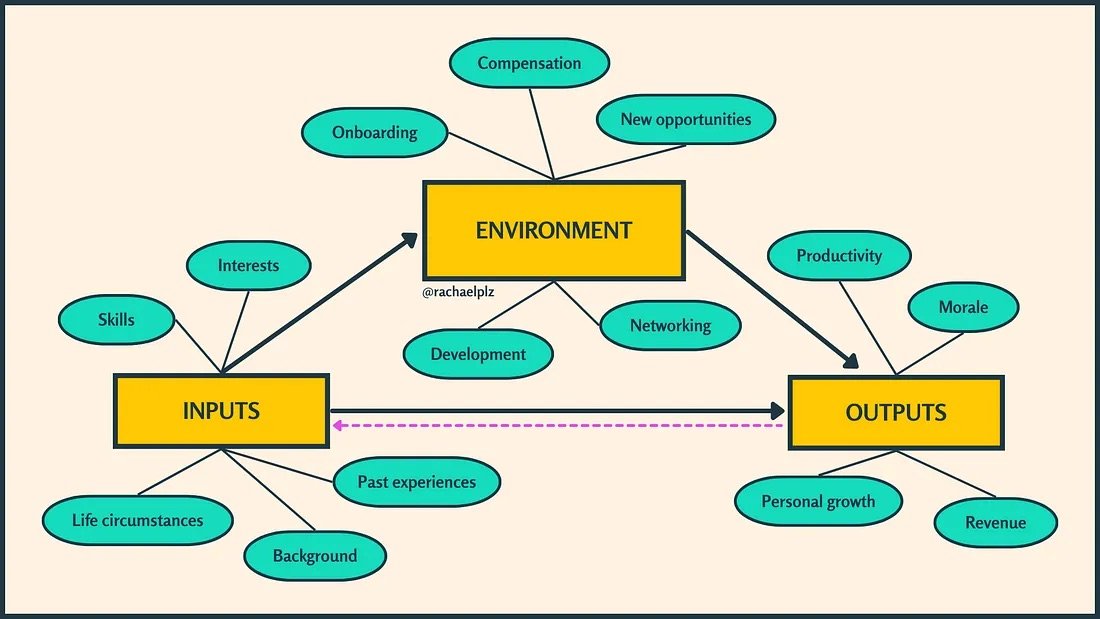

My career started in higher education. I worked at several colleges and universities, and I have a masters in higher education administration that I got a few good and underpaid years out of before switching careers. One of my first classes as part of my masters was wholly focused on different theories of learning and development. One that I think about often, even a decade later, is Astin’s Theory of Student Development. Astin uses an Input-Environment-Output (or “IEO”) model to conceptualize the experiences students enter college with, the environment of learning, and the outputs generated from this funnel. This paper talks about it much better than I can, but here’s the idea:

The IEO Model

This model in its basic form isn’t new — there are similar input-output models for management, feedback loops, economics, etc. It likely has an entirely different name within gaming mechanics which, from my understanding, has a term for literally any concept.

But back to people operations.

There seems to be this understanding that talent is just an input in a broader model of organizational success. Yes, each individual has potential and past experiences and references, but it is as though the experience of onboarding is what makes them a valuable team member. The focus is solely on results with no care for the environment that drives that output.

An abridged talent strategy

The issue with this line of thinking is it removes the continual personhood of the team member. It can quickly go from “We hired this person because ABC” to “This team member will get us to XYZ.” Both can be true, but the former is forgotten. It also bypasses the idea that what is happening in their own lives can and will affect their performance. An important part of an IEO model is that Inputs can also directly affect Outputs, even if you blind yourself to the Environment itself.

In my opinion, a broader talent strategy is necessary, one that holds the nuances of people and change.

Let’s put it to life.

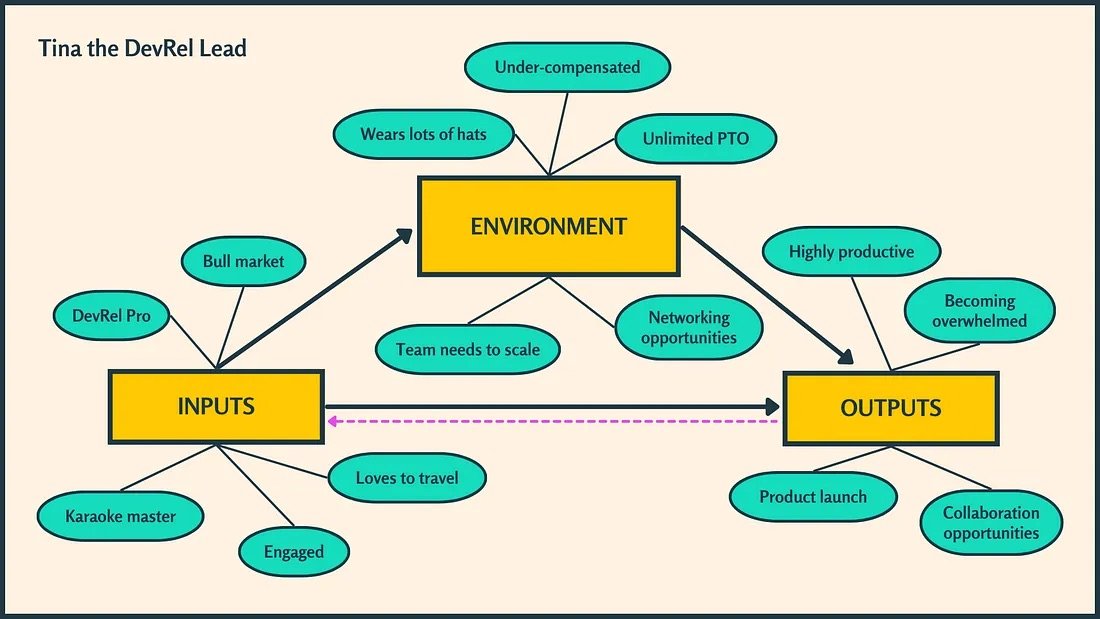

Let’s say Tina is hired to join as a new DevRel Lead. She was hired because of her vast skillsets in development and growing communities. As she joins the team, she is (admittedly) under-compensated but provided with wonderful opportunities to network and develop her skills. Overall, she is very happy and quickly shows her value to the team and to stakeholders. She becomes well connected in the wider ecosystem and often mentors junior developers. This excitement and engagement gives her a sense of fulfillment even in her personal life, and she feels a general sense of work-life balance in a way she hasn’t before.

However, over time, things start to shift. Her skillset is growing along with other interests she’s picked up over time. Because of her expanding skillset, her professional responsibilities are also growing. She’s attending conference after conference — sometimes specifically for work, other times simply from fear of FOMO. While still wildly productive, she’s losing steam when it comes to motivation. She realizes she’s only taken two days off over the last 6 months — despite there being an unlimited PTO policy in place and a flexible working schedule. The market has been down for quite some time now, and she’s not blind to impacts that has on her workplace. She’s realizing it’s time to advocate for some change. She pulls back on attending conferences and proposes a raise based on all her success and growth.

Now, let’s step back.

There’s a lot happening here and a lot of moving pieces that are simultaneously feeding off of each other.

Lisa’s experience in an IEO model

Lisa opens her laptop each day with a generally positive outlook. She enjoys her team, and she believes in the mission of her organization. But there are things both within and outside of her control that are affecting the harmony of her life. Likewise, there are things in and out of the organization’s realm of control affecting goals and outcomes — and each of these nodules have various levels of impact.

Just as Lisa must take responsibility for the inputs she has control over, an organization must take responsibility for the environment it is creating. For example:

If utilizing an Unlimited or Flexible PTO model, the organization ensures the culture is reflecting proper and healthy use of it.

Team members are fairly compensated.

Expectations around responsibilities are clear.

Teams are given the proper resources to meet their goals.

And the list goes on.

What do we do with this?

The answer likely isn’t to write new policies or reform a strategy around talent and people success. It doesn’t mean creating new OKRs or really implementing any immediate changes.

It starts with a mind shift across the organization. It begins with leadership (whether formal or not) taking on a mindset toward a culture of care and compassion.

It requires candid reflections and conversations around personal and organizational loci of control. It asks individuals to take stock of what is needed by them, for them. It demands organizations understand that change may be necessary to achieve the results they want.

Organizations may or may not care whether their team members are fulfilled or living within manifested ikigai from day to day. And truthfully, individuals may not expect compensated work to fulfill a greater purpose in their lives. Regardless, though, it behooves organizations to take an approached to nuanced care. Because at the end of the day, it can lead to better outcomes.

This isn’t about people liking their jobs. It is about adjusting an environment that leads to success. It isn’t about better benefits or bigger budgets but about providing teams with what they need to be successful.

There are easily a dozen arguments against this, but I’m just naive enough to believe this could work anywhere.

In my opinion, what’s difficult about this isn’t that it takes time or some creativity. It’s difficult because it requires empathy. It needs managers to think past productivity metrics and take responsibility for organizational barriers that make it difficult for people to succeed. It takes individuals understanding the weight of personal responsibility and how it can lead to a great sense of empowerment. But it does also take time and creativity.

But if you believe in your product, those investments are worth it.